In England, and Poland, and Spain, and France, you turn the peasants in a grisly dance, transmuting land to property "private," by gun and by sword, migration you drive it.

Then turning to soil, loved and engaged, upon the indigenous, war you wage, driving the peasant to the New World, displacement, now is the dance you twirl.

And when the peasants and paupers want paid, to another place, slaves you made, from people who live in and love their homes, you fill the oceans with their bones.

From England, and Poland, and Spain, and France, a triangle forms your frightening dance, for value and guns, and promises riven, to each oppressed people perplexity given.

And ultimately, now, generations taught, to prize the dancers with whom they once fought, who stole the land, the lives, the hopes, and hung their grandparents upon ill ropes.

But if we together, stand and say no!, repairing our past, our future aglow, reject the rich and their lying lies, perhaps we can fairness, bear through clear eyes.

The homeless be housed, the hungry be fed, though the rich, themselves, may flee in dread, the workers will dance a dance they are due, though we end the lie, we savor the true.

I wrote this poem reflecting on the history that got the globe to the brink of collapse. The history begins with the peasant classes across Europe being forcibly removed from common lands, which they had farms for the pre-capitalist era's nobility and aristocracy. It had been centuries since much changed for peasants, and the way of life, living and working the clean land, living by the seasons, eating organic food, etc., until the rich among the merchant class, aristocrats, and nobility (now the early bourgeois) began transmogrifying the land to private property. Marx studied this history in Scotland, explicating it with a specific example. "'Klaen', in Gaelic, means children. Every one of the usages and traditions of the Scottish Gaels reposes upon the supposition that the members of the clan belong to one and the same family. The “great man”, the chieftain of the clan, is on the one hand quite as arbitrary, on the other quite as confined in his power, by consanguinity, &c., as every father of a family. To the clan, to the family, belonged the district where it had established itself, exactly as in Russia, the land occupied by a community of peasants belongs, not to the individual peasants, but to the community." The process involved the "robbery" (to use Marx's term) of church property, of the commons, and "fraudulent transformation, accompanied by murder, of feudal and patriarchal property into private property."

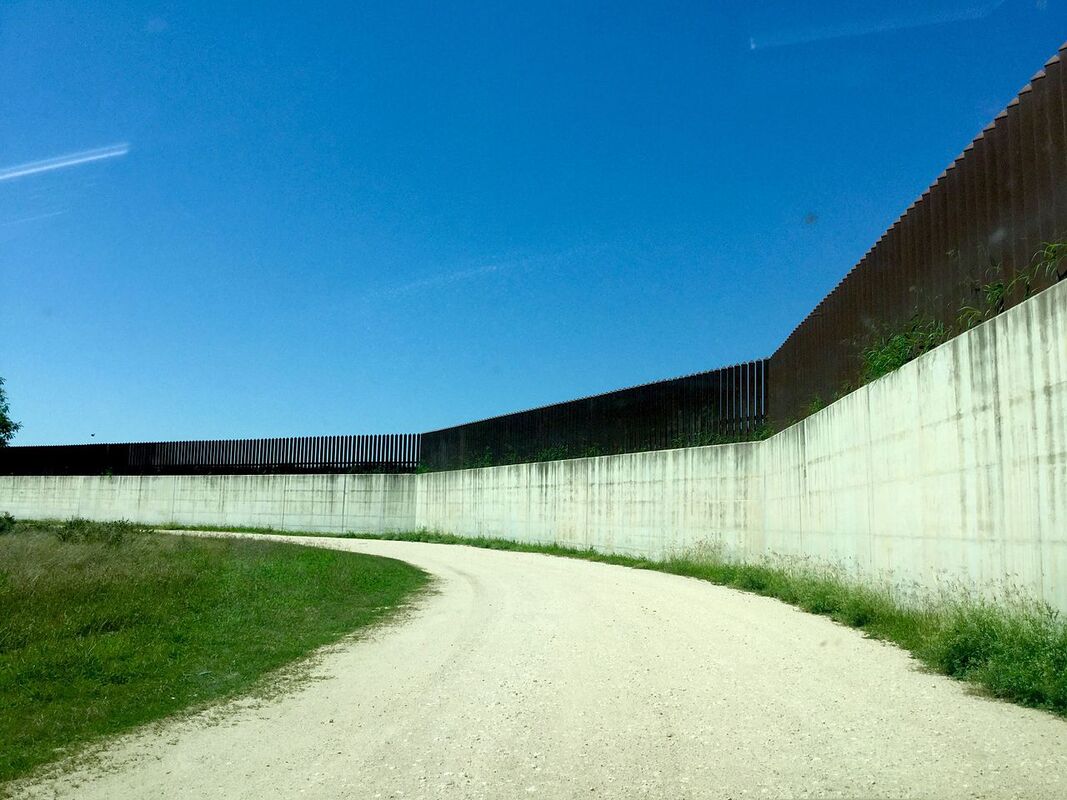

Next in my poem I turn to the ancient lands the new bourgeois labeled as the "New World," which they claimed was uninhabited and open for European migrants, which were mostly uprooted peasants hoping to make a living, some of which hoping to join the increasingly global bourgeois class. Few succeeded, and most found only poverty in the new American cities and towns.

When the American farm-workers wanted fair salaries for their labor, the bourgeois of Europe and America fixed their gaze on Africa, where they robbed people of their soil in the Atlantic slave trade. However bad conditions were in the child-labor dominated factories of the American North, the slave-based economy of the American South and the Caribbean was worse, leading to many rebellions. Howard Zinn draws out an example, the great rebellion of 1676. "Bacon's Rebellion brought together groups from the lower classes. White frontiersmen started the uprising because they were angry about the way the colony was being run. Then white servants and black slaves joined the rebellion. They were angry, too-mostly about the huge gap between rich and poor in Virginia." Most people in Virginia supported this rebellion, and, as a result, it planted in the bourgeois (including the English nobility involved in the profits) the idea that dissecting the underclasses, getting them to focus on identity above solidarity, was the only way to protect their wealth and class from rebellion. We see this active today, particularly propagated by wrong-minded activists who would see bourgeois like Bill Gates (net worth 126.2 billion USD) and Elon Musk (net worth 157.4 billion USD), or even Donald Trump (net worth 2.5 billion USD) as on their side before the uneducated masses.

So the dance needs a be replaced by a new dance. The grisly dance of capitalism must be replaced by another dance. USSR-style communism was blatantly NOT a replacement, but an ecologically destructive government that empowered the powerful, then starved and killed the oppressed. But that doesn't change the fact that capitalism must be replaced. 8.9% of the globe is starving under capitalism, while the three billionaires I named could easily feed them all and still be billionaires. They could still be far wealthier than Scrooge McDuck, diving in his hoard of gold, and end all world hunger. Capitalism has created the 1.6 billion world homeless. All so a small bourgeois class of billionaires (less than 3,000 individuals in the world) can hoard unimaginable capital. And Bill Gates offensively has a new book on sustainability. Bill Gates IS the ecological problem, with his stocks in dirty oil and made his money by poisoning the earth, sickening children in the Niger River Delta. We must look seriously at our history and do better than this. We just cannot afford the nearly 3,000 global billionaires our economy currently supports while causing so much suffering.

DS

Link to Niger Delta Oil Spill on Wikipedia: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2e/Oil-spill.jpg

RSS Feed

RSS Feed