The advantage of skunk cabbage

I won’t claim it’s a saint

But in March’s scene, this striking paint

Unpleasant title, excellent plant

Generating warmth that others can’t

Yesterday, I went for a hike around Lake Perez with my family. I took this photo, and wrote this poem. Walking the boardwalk over the swampy section, we saw the skunk cabbages growing. A perennial wildflower, skunk cabbage creates its own heat in March to melt the snow around it as it grows. The reddish purple, pod-like growths were all over the ground, bringing color to the brown land. Skunk cabbage has a distinctive smell, to say the least, which though offensive to humans and other mammals, attracts bees, butterflies and other insects. While I wouldn’t recommend bringing them into your garden or yard, the skunk cabbage is a helpful part of the wild ecosystem.

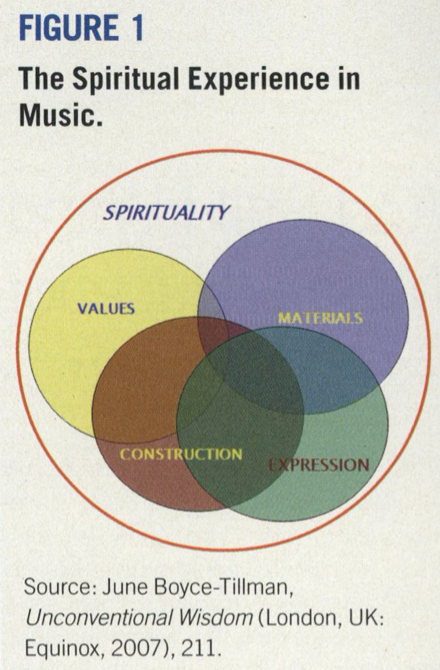

So too is my vision for music education. Music educators can find themselves as helpful parts of the overall school environment—teaching music, which is essential to the lives of children and many adults, and, employing an interdisciplinary focus, teaching students to holistically consider all challenges schools consider. The skunk cabbage doesn't float above the mud like some perfect angel, but resides in the mud, benefiting many others in its distinctive ways. I don’t see this approach as emphasizing “extra-musical” aspects of music education, because music has always, since the time the first homo sapiens sang and danced around campfires hundreds of thousands of years ago, been intertwined with other "disciplines" such as visual arts, storytelling, and science. This is where the old aesthetic music education philosophers erred. Music is not one thing, and these other disciplines found in schools essentially something else. Music is all of these things.

Younker and Bracken studied the pedagogical possibilities for birdsong as thematic-based curricular connections between science/ecology and music with fifth-grade students. Ultimately, students composed birdsongs, and the importance of the project was strengthened by the experience of “doing.” They conclude, “we live in a world of projects that requires ongoing, working knowledge of the interrelationships among disciplines” (p. 50). I would argue, their approach is not "music for musics sake," but music for life's sake, which is far more meaningful.

I believe this interdisciplinary understanding of music education is true. But also, I want to push the bar of interdisciplinarity. Interdisciplinarity implies distinct disciplines that exist, sort of like Plato’s forms, that we can bring together. This, I suspect, is NOT the intention of interdisciplinary-minded music education scholars. Instead, I think the natural—if I can use that word in a less-than-natural way—state of things is connected, and we have historically, through schooling, created disciplines (classes, subject-matter, and curricula) for our ease as educators. Disciplines make schooling easier, so we reinscribe the idea of disciplines evermore each schooled generation.

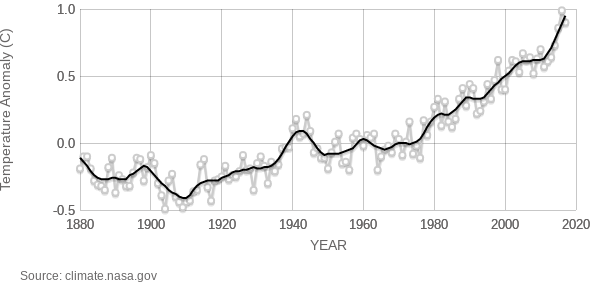

I also don’t think it’s for students’ ease or use. Thinking of mathematics, and reading, and musicking, and storytelling, and cooking, and gardening, and all of the other important “disciplines” of living as separate or separable doesn't seem like the best approach. It’s a big part of how we got into this ecological mess in the first place. Engineers don’t art, dancers don’t nuclear science, mathematicians don’t ecosystem, etc. Like horses with blinkers on. This is not picking on any single discipline or individual as doing worse than another—but rather a questioning of the disciplinizing of the lived world. Interdsiciplinarity can serve as a counterweight to centuries of disciplinizing our world, but ultimately I think we need a deeper conception, one that is more fully anti-disciplinizing, de-disciplinizing, or antithesis-to-disciplinizing.

DS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed