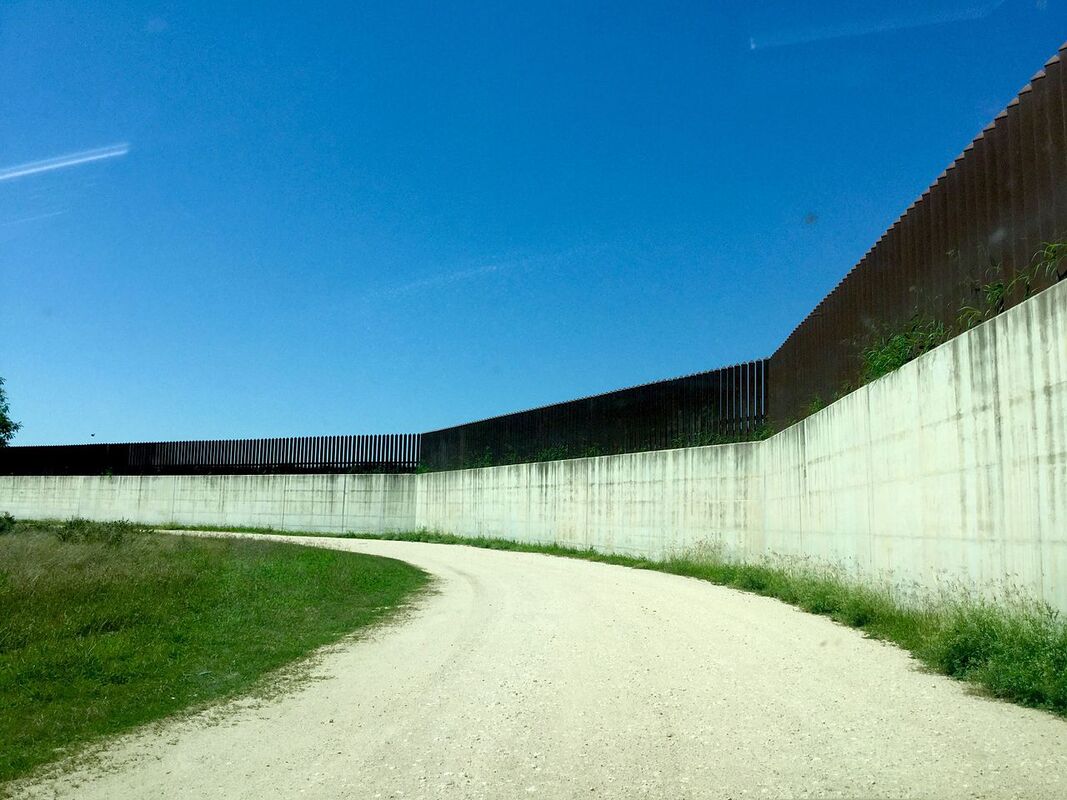

“One day this wall is going to fall … This is a scar on our mother” (Israel Aranda, in Fandango Without Borders). Fandango fronterizo (border fandango) involves a communal musicking experience on both sides of the wall dissecting California, US from Mexico. “The border fandango is a symbolic event. We’re trying to show how music can build community, even when communities are separated. Son Jarocho is the perfect music for that, because it’s all about being together with friends. The community of friends who play Son Jarocho is growing in both Mexico and the U.S., and the fandango fronterizo reminds us that we are one community despite the barriers that divide us.”

This wall negatively impacts human and non-human animal communities. In fact, the wall effects 89 endangered species and potentially impacts 108 migratory bird species. These are not separate issues, but one challenge. That challenge is linked to national identities that overpower bioregional and local ways of being. While people, in community, cultivate diverse ways of being, diverse musics, and offer hospitality, nations offer walls and prisons. Nations and global governments work, for the global billionaire class, to transmogrify people into population. These structures kill diversity.

I heard about Son Jarocho and fandango frontierizo in specific in an interview Kevin Shorner-Johnson conducted with the Chicana artivista Martha Gonzalez on his Music and Peacebuilding Podcast. In fandango frontierizo people come together to recognize and live the reality of community, and challenge the artificiality of national borders for people living on soil. In contrast with industrial musical models, in which musics are enclosed, collective songwriting and community musicking are essentially a practice of what Gonzalez calls convivencia—living with one another. At the core of living together, of living on soil is the practice of the co-living of “place, commons [and] community” (p. 3). What Madhu Suri Prakash and Gustavo Esteva labeled staying well rooted. This is the essence of the sustainable and regenerative cultures that are resisting capitalism. This is ecological musicking, honoring and learning from our Mother Earth, our animal and plant brothers and sisters, and diverse human ways of being. This is the anticolonial practice so many music education scholars are searching for. Colonialism is, at its start, a theft of land from people (e.g., for Indigenous peoples in the U.S.) and a theft of people from land (e.g., for African peoples taken by the slave trade) that has poisoned the land, our self-esteem, our labor, and our relationships to one another, our solidarity with other oppressed peoples of earth, for quarterly profits.

As a rural child, if memory serves me well, I first learned Mexican music when my Geography teacher at St. Bernard’s Elementary School in Hastings, Mr. Rodriguez, taught the class two traditional songs, La Bamba, which is a Son Jarocho song that was popularized in the U.S. by Ritchie Valens, and the Son Huasteco song, Cielito Lindo, which he accompanied on the accordion. Places thrive on diverse local cultures. What they don’t thrive with are nations, their borders, their jails, their militaries. In the US, children are infamously kept in cages at the border—when in truth, journalists aren’t permitted inside camps that house migrants and refugees today (many who are fleeing the climate crises rich nations in the Global North exacerbate).

Abrahm Lustgarten of the New York Times calls this the “great climate migration.” For instance, crops are failing in Guatemala due to a “confluence of drought, flood, bankruptcy and starvation.” The model shared predicts migration to the US will increase substantially with climate change. “In the most extreme climate scenarios, more than 30 million migrants would head toward the U.S. border over the course of the next 30 years.” This can an opportunity to enrich Pennsylvania’s local culture. However, national politicians and global billionaires work to stoke fear. It is fear many poor people have (the 14.1 million White poor, but also many of the 9.5. Hispanic poor, the 8.1 million African American poor, and the 600,000 Native American poor in the U.S.), in the supposed-richest economy the globe has ever known, but which has left them starving. Solidarity can be found. People living together on soil. Musicking together. Farming together. Going to church together. Eating together. Guarding our shared Mother Earth together. Being together, in their own ways of talking and being in the world. On soil.

Today, in Emsworth, PA, Holy Family Institute houses unaccompanied children who cross the border. As an immigration lawyer who works with the institute says, “A lot of them are frightened. A lot of them are scared. They’re just looking for a little love like any child around the world, a little bit of caring.” While nations, as they’re currently set up, fail to care for children; more than that, they initiate the refugee crises to enrich global billionaires, ordinary people can lend a hand where they can. Pushing governments to act (even if they are in the pockets of global billionaires) and enacting local, individual and communal change are not at odds. Some possible bad-actors in socialist discourse have suggested that the only hope is top-down. Well, this isn't so. As a student of educational philosopher Madhu Suri Prakash, I look to the grassroots. To soil. To those protecting clean water, air, parks, and resisting eminent domain and other stools of enclosure in localities around the globe, each in their own ways, artistic and activistic and communal.

Music educators, too, can lend a hand, however we can. I resist a music education that encloses music and encloses what it means to be musical or a music teacher. Co-conspirators Vincent Bates, Anita Prest, and I suggest, drawing on indigenous knowledges and ecological thought. In a recently published chapter on cultural and ecological diversity, music teachers can forge egalitarian relationships, communal responsibilities, cultivate reverence for our ancestors and nonhuman living beings, topographies, and nurture musical practices that regenerate our local and bioregional ecosystems. I am happy this work is available to be read. What the industry calls open access. Open access may not be the best model, but it is better than others, and we fight capitalism from within the belly of the beast. We cannot do elsewise, as capitalism is the dominant ideology on the globe today. From within, we try to create new commons. When our internal voice says to make profit by enclosing, we resist.

The border walls are scars on our mother. Mother Earth. Let’s heal that scar. She will teach us how.

DS

Link to image of the Texas border wall ... (isn't it UGLY! Deadly so. But even so, do you see those grass roots working, in their gentle, humble way, to tear it down?): https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f1/United_States-Mexico-border-wall-Progreso-Lakes-Texas.jpeg

RSS Feed

RSS Feed