Zen: “Chinese Ch'an Buddhism. a Mahayana movement, introduced into China in the 6th century a.d. and into Japan in the 12th century, that emphasizes enlightenment for the student by means of meditation and direct, intuitive insights, accepting formal studies and observances only when they form part of such means. … (Lowercase) A state of meditative calm in which one uses direct, intuitive insights as a way of thinking and acting.”

Especially in the 20th Century, Zen (and zen) came to the U.S. in expanding Buddhist communities, in the art of beat poets such as Gary Snyder, and through the work of popular Catholic writers such as Thomas Merton, Thomas Berry, and Richard Rohr. It became a focus of Americans interested in self-exploration and working against increasingly fast-paced, technological, work-focused life. Not all who practice Zen in the United States were interested in converting to Buddhism; and ultimately this led to non-religious zen practices (including to whitewashed Western mindfulness movements that don't even refer to or give gratitude for their practice's East Asian origins), and to zen's widespread practice in everything from martial arts to motorcycle maintenance. Zen is, in its 21st Century understanding, applied to specific activities in everyday life, including work and play. It is not unreasonable, then, to suggest there is a zen to music teaching; or at least that zen can help us who teach music.

Mu: “Not have/without.”

“A monk asked Jōshū in all earnestness, “Does a dog have Buddha nature or not?” Jōshū said, “Mu!” (Kōun Yamada, The Gateless Gate, p. 11)

Zen koans, such as those collected by Kōun Yamada, serve as paradoxical stories for meditation. Time must be spent with them. Contemplating. Rolling them over in the mind. I cannot tell you what the meaning is in any complete way. Explanations (including those provided in Yamada's book) are always incomplete. Koan's help people attain enlightenment, gain insight to hidden things, and achieve peace of mind and body. I draw attention to this koan because, for me, it enlightens (gives light to) my definition of music--the intentional experiencing of sound—which is an anti-anthropocentric definition created to open space for music teachers to consider the musicking of non-human animals more on-its-own-terms. Does a dog have music or not? Mu! Rather than saying dog animals are without music, the more robust idea of Mu is introduced. (I also like that Mu in English is the beginning of the word Music for my modification of the koan.) This is the same for human animals. Enlightenment is attained through Mu. When we learn an instrument, or improve our singing, we enter a state of being that can be described as nothingness. No-thing-ness. Things become unimportant. If we are thinking about things (what to have for diner, where to purchase a new hammer, whether the boss will shout at you) in a performance, we often mess-up. There is too much on our plate. Too much liquid in our cup. When we enter a state of nothingness, Mu, we music; and many believe dogs live in Mu every moment of every day. They have already attained the nothingness for which we strive.

“We can begin falling in love with the Earth right now. … Mindfulness is the continuous practice of touching deeply every moment of daily life.” (Thich Nhat Hanh, Love Letter to the Earth, p. 86)

Every day I practice my instrument, or sing, or record a soundscape I find interesting (and post to YouTube), I fall in love with Mother Earth. The wood of my marimba, or metal of my vibraphone, came from Mother Earth. When I touch it and it resonates, it is like the voice of my God speaking the inexplicable language of Mother Earth (see Satis Coleman, The Book of Bells, p. 20). Unseen human animals put their sweat into fashioning Mother Earth's body into beautiful instruments, and now I create my art on these instruments. I practice zen when I touch my instruments mindfully, aware of all of these ecological and historical connections; to human and non-human people and place. Every moment of musicking is an opportunity for zen insight.

“The lakes hidden among the hills are saints, and the sea too is a saint who praises God without interruption in her majestic dance. The great, gashed, half-naked mountain is another of God’s saints. There is no other like him. He is alone in his own character; nothing else in the world ever did or ever will imitate God in quite the same way. That is his sanctity.” (Thomas Merton, When the Trees Say Nothing, p. 30)

The tree and the mountain who offered wood and metal for my marimba and vibraphone are saints, who imitate God in ways I cannot. But now we imitate God together, a collaboration even when I see myself alone in the practice room. I am not alone. We can imitate God as a musician and music teacher. When I introduce students to these instruments, I can help them approach it with full mindfulness; aware of the ecological and historical connections to people and place. I can help them recognize the sainthood of the tree and mountain bodies on which we music. We can slow down and truly experience each sound. Slowly. Livingly. Lovingly. When we do this, we teach music as if it were a zen practice. We zen.

“But musicians also live in the real world and in various discernible ways the sounds and rhythms of different epochs and cultures have affected their work, both consciously and unconsciously.” (R. Murray Schafer, The Soundscape, p. 103)

Zen is a practice of bringing the unconscious to consciousness. Enlightenment. The mysterious becomes, in some way, experienced and understood. The Canadian composer, R. Murray Schafer, who passed away this week, drew music teachers attention to the musicality of the soundscapes we find ourselves in every day. Mother Earth is one giant, ongoing musical composition. One job of music teachers is helping people become aware of that composition, and to help improve its musicking. That which we had previously ascribed to mystery became slightly less mysterious. This helps transform our music teaching practice. This understanding also provides an opportunity for gratitude. Graciously, the cup of consciousness is filled and emptied again and repeated again, and gracious for the student sharing the musical experience, the student being a teacher, and the musicking world in which we find ourselves, amazing, unrepeatable nothingness, that is Mu and music, is created and disappears into eternity in every moment, and in none.

DS

More in this blog:

See Post 8: Chinese Philosophy, Ecocentrism, and Eco-Literate Music Pedagogy

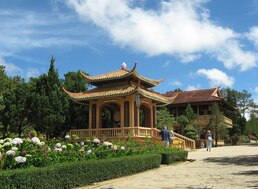

Image: Truc Lam Zen Monastery

RSS Feed

RSS Feed