I and He, by Marion Cuthbert

I told my child

God could make worlds.

Delight was a fountain in his eyes,

Remembering his own secret world

Which he might turn to in any wakeful hour

Or enter in a dream

It was good to know

That God, too, could make a garden

Or a friend.

I told my child

God was not greater than the rules.

This seemed right to him--

To know that things are as they are

And will not change except as they must

Because of what they were created for

If you have a little puddle of water,

You have to play in it fast.

Putting your hands over it won’t help long

Because little puddles go back to the sun.

I told my child

God was always becoming.

He said this was true, of course, because

All alive things were growing all the time.

When he was a little boy, he thought

Lilacs die forever, but they don’t,

They just like to come before us in spring.

And then, too,

He, himself, was four, going on five,

And after that would be six.

The Harlem Renaissance poet Marion Cuthbert (1896-1989) also wrote the 1936 book We Sing America (discussed by Marie McCarthy in her presentation Black Music and Music Education in the Mid-Twentieth Century during the most recent NAfME Conference), which depicted “stories of outstanding African-American achievements with descriptions of present-day racial injustice,” and a Ph.D. dissertation at Columbia University, Education and marginality: A study of the Negro woman college graduate, which became a foundational document in that field of study.

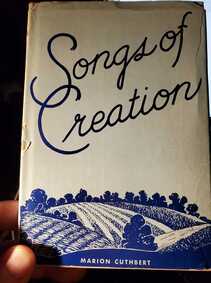

The poem I and He opens her book, Songs of Creation. [See the photo I took of the book cover]. Drawing together parenting an African American child, I and He contains subtle and beautiful references to how to survive psychologically, how to find happiness and beauty in the present moment. Cuthbert's spirituality and connection to nature speak deeply to me. Layers upon layers of beauty and strength.

And for music educators today?

Green Hip-Hop is a “small genre,” but growing. There are some artists who are writing mostly eco-conscious music. Markese “Doo Dat” Bryant was identified as the lead among these. Growing up near a Chevron plant influenced his ecological understanding and his music. Listen to this Living on Earth show about Green Hip-Hop, and listen to Markese’s 2009 song The Dream Reborn (My President is Green). “Look, I’m from the hood. We need better food and better air, you probably wouldn’t never care. Why?! You ain’t never there. … My president is Black, but he’s gone Green.”

For many of my students, Black, White, East Asian, and other, Hip-Hop is the primary way to think and act musically. When we song-write in class, many of my students rap. I leave the choice to sing or rap up to them. Environmental science scholar Michael J. Cermak writes about the opportunity for Hip-Hop to be central to cultivating critical ecological literacy. In his work, students composed green hip-hop lyrics (more than 200 compositions collected over four years). Of particular interest, he writes “when student-produced texts are refined they can become teaching materials for other students. … This student-to-student transmission of environmental knowledge is a crucial step in mitigated the potentially problematic role of cultural insensitivity in environmental education, and one that allows texts to grow organically.”

There are other Green Hip-Hop pieces music educators can make themselves familiar with, such as Mos Def’s New World Water and Will.i.am’s S.O.S., but, since hip-hop is a conversation between artists, providing space for students to take the lead, to center their own experiences (rather than another global industry), and create a truly local database, an ongoing conversation to share from one year to the next, might be an authentic and ecologically affirming way to teach hip-hop in communities and schools. This can become central to an educational approach that treats students not as waste or as consumers, but as artistic beings living in resisting a problematic society.

DS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed