Deep in my soul

the old songs are waking

Inspired by nature

love of our earth

She who came first

Her old bones are quaking

I open myself

I will not deny my voice

We were all brought forth

out of the darkness

The forest, the seas

the mountains and shores

Stomping a beat

that bubbles within me

Wind carries my dance

an old tune of unbroken lores

My sister, Christine Hartman, wrote this poem yesterday in our family Facebook group. Indeed Mother Earths old bones are quaking.

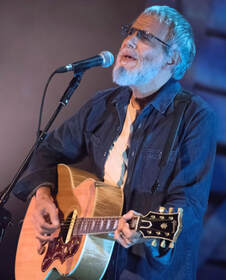

When I think of the idea of old tunes, and unbroken lore, my mind goes to the folk song tradition, which, though now is a pop music genre, feels connected to an older song tradition. The type of balladry used by singers like Joan Baez, Odetta, Lead Belly, Bob Dylan, and Yusuf Islam, simple singer and accompanying string instrument, would have been in-place in medieval Europe, in ancient African civilizations, in the ancient Israel of David, and in the ancient China that gave birth to Laozi—though the string instrument of choice would be different in each case. Laozi writes: “People follow the earth. The earth follows heaven. Heaven follows Dao. Dao follows what is naturally so.” People, Earth, Heaven and Nature.

And in the Psalms David sang: “Bless the Lord, O my soul. The trees of the Lord have fruit in abundance, the cedars of Lebanon that he planted. In them the birds build their nests; in the fir trees the stork makes its home. The high mountains are inhabited by the wild goats; in the rocky crags the badgers find refuge.”

Nature, home, and sustainability have been themes of folk musics since the start. In a more modern folk song, Yusuf Islam, in “Where Do the Children Play” sings, “Well you’ve cracked the sky, scrapers fill the air. But will you keep on building higher ‘til there’s no room up there? Will you make us laugh, will you make us cry? Will you tell us when to live, will you tell us when to die? I know we’ve come a long way. We’re changing day by day. But tell me, where do the children play?”

In popular music, lyrics serve as the core of the musical experience. The essence. This may come as a surprise to music educators, who have, I think inadvertently, been taught that music education is about teaching the sonic/theoretical aspects of musics—chord relations, rhythms, form, dynamics, etc.—but when I teach popular songs to my students in MUS 8 (which is an introductory music theory class for undergraduate non-majors), their experience with music (and I always begin with student experience) is almost always with the lyrics. Words in rhythm and melody. Not three separate ideas but one: words/rhythm/melody. Every now and then I’ll have an EDM fan who experiences “the beat” first; but 99% of the time, it’s a meaningful, evocative, feelingful lyric that draws people to music. Music educators ignore this at their own, and the field's, loss.

In an upcoming presentation at the Music, Spirituality, and Wellbeing Conference (in July), I’m working with Gareth Dylan Smith to understand a project we have worked on. I am writing poetry, and he is creating drum tracks to accompany those poems. Here’s a link to his YouTube page, where he posted the interpretations of the poetry from my book, Eco-Literate Music Pedagogy. What might this mean for music education?

I have students in MUS 8 improvise/compose two songs during the semester, as they get their heads around various music theory concepts. In the first, students write and read poems (outside/describing soundscapes) and create beats behind them using found-sound instruments. See my 2019 article on waste and popular music for my philosophical thought on why instrument construction can serve as a resistance to metaphorical and material waste in popular music education.

In the second group presentation, students turn the approach on its head, thinking about the forms used in various popular songs, and creating beats, chord patterns, and improvised solos using apps and other technology (which they share and explain during their presentations/performances), and create/add lyrics that the music inspires later. They can sing or rap these, as is appropriate to their style. By the time students finish MUS 8 in my sections, they not only have an [hermetic] understanding of sonic music, but a practical experience of musicking; and they understand the embeddedness of lyric-writing to the musical process. Not all musics have lyrics. But most does. It always has. Our first musical instrument is our human voice. Singing likely kept us running together 200,000 years ago when humans were persistent hunters in Africa (some folk still are), and the same singing scared away predators at night and joined us together in communion. Lyrics can and must be meaningful. This is likely why folk musicians were addressing the ecological crises long before school music educators and scholars. Music and words aren't two different things. We have ignored words for too long.

DS

Image of Yusuf Islam cropped and retouched from original by Bryan Ledgard as allowed per Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) licensing. link: upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a7/Yusuf_Islam_BBC2_Folk_Awards.jpg

RSS Feed

RSS Feed