While the publication of my book five years ago has generated some alternative expansions of what it means to teach music for ecoliteracy, (such as by Vincent Bates, Tawnya Smith, Atillio Lafont di Niscia) there have not been explicit objections to the idea of teaching music for ecoliteracy. One objection, sort of, that was made explicit came from Lise Vaugeois’s 2019 review of the book. Vaugeois is a senior scholar whose long body of work on sociology, social justice, colonization, and institutionalization in our field speaks for itself. And Vaugeois has put money-in-the-mouth, as the saying goes, becoming active in Canadian election-politics. What an honor to have my book read and critiqued by a scholar whose voice I have long respected!

Vaugeois identifies the separation of the “cultural” from the “political” as problematic. Quoting page 91, this separation is described as “an unnecessary, and false dichotomy.” Discussing the example of corporations funding false science, Vaugeois continues, “it is not simply cultural misguidedness that is in play but a strategic use of misinformation designed to maintain control over existing concentrations of wealth and power.” I agree with Vaugeois 100%, that it is not “simply cultural misguidedness” but strategic, and political. If this dichotomy emerged in my book so strongly, I would agree wholeheartedly with this critique, and my book would need revision. However, I had not understood my writing as presenting an either/or dichotomy, but rather a political viewpoint understood through the lens of culture—where both exist, but that policy emerges from culture (rather than culture from policy, or both emerging as separate, dichotomous domains). The example presented is not "simply cultural misguidedness" but it is cultural to the extent that policy emerges from culture, not vice-versa. I present an ecosystem, and not policy-sans-culture nor culture-sans-policy. Culture is the root, and politics the fruit.

Where does this seeming dichotomy emerge? In Chapter 5, in which I am attempting to draw together previous chapters to recommend a possible spiritual praxis I share an idea initiated by Wendell Berry. Here is the section quoted by Vaugeois, but more fully on page 91:

Quote from my book: “Wendell Berry (2010) appropriately notes that ecological challenges are not political, but cultural at root (37). Policy, then, without parallel change in cultural beliefs, will be insufficient. In my philosophy of music education on soil (outlined in Chapter 1, “Philosophy on Soil”), the cultural disconnection that led to our ecological crises is understood as a spiritual problem, and requires a spiritual reconnection to neighbors, to actual places, and to an expanded view of self that values non-human life forms and their musicking intrinsically (Chapter 4, “Deep Ecology”).”

What I recommend on this page, then, is not a dichotomy, but for parallel changes, political and cultural. As I say, policy changes will be "insufficient" because the next generation of policy-makers will just reverse the previous. Such happened with the lands President Obama set aside for conservation, which were then de-protected in the first days of the Trump administration. Policy had done a good thing for Mother Earth, but no cultural change had happened, and policies changed. The life of a forest or ocean or the sky cannot have value only when it's politically viable. The U.S. government has only stood for a little over 200 years, and while 200 years ago seems like a long time ago, it is a blink to Mother Earth. Where I agree fully with Wendell Berry is that the ecological challenges are cultural at root. That policy is also cultural at root. Policy/politics is the fruit that emerges from the roots of culture.

It seems that it might be a common worry for those who would focus on policy, rather than culture, that those to suggest culture is at root, political action would be somehow unlikely.

However, this is an unwarranted concern. For instance, Wendell Berry, who in his writings as given clear supremacy to problems of culture above those of policy, has a long history of political action, which perhaps began with his 1968 “Statement against the War in Vietnam,” delivered at the University of Kentucky, his nonviolent civil disobedience against the construction of a nuclear powerplant in Marble Hill, Indiana, in 1979, his 2003 “Citizen’s Response on the National Security Strategy of the United States,” critiquing the Bush post-9/11 international strategy, and his action on the “50-Year Farm Bill” in 2009. Each of these actions were political, and his understanding of his political actions were at root cultural. And each action had major impacts on the long-term political efforts to conserve Mother Earth. Similarly, Vandana Shiva, also referenced extensively in my book, emphasizes culture as the root to our ecological problems, and has a long history of political action.

Similarly ecoliterate music education is political action, which understands politics as an expression of culture, not as a separate domain. On the same page (91) of the book being criticized as not being political, includes a critique of ExxonMobil for not investing in sustainable energy in 2009 after big oil’s claims to making investments into solar, geothermal, and wind energies; and university’s political choice to emphasize technological fixes that have often made our ecological crises worse, not better. This single page of the book discusses fracking, mountaintop removal, and deep water and Arctic drilling, political concerns that are seldom, if ever, brought up in music education scholarly discourse.

Though my career higher music education has been precarious, serving as an adjunct instructor in a dying Arts and Humanities department (now greatly reduced for budgetary reasons) and now as a day-to-day substitute teacher, I have also tried to put-my-money-in-my-mouth, in my own small political way, having shared teaching for ecological consciousness and action with graduate students at The University of Freiburg, Westminster Choir College, The University of South Florida, and Eastman School of Music; and taught students at the undergraduate and Middle School level to better understand the ecological challenges we face, through music. I have also (non-music-related) participated in political action on the streets, in my community. If the danger of understanding the political through the lens of culture leads to inaction, I don’t see it happening in reality. Rather, Wendell Berry and Vandana Shiva have long been leaders in political actions to protect the environment/ecosystems. I also suspect those who do not understand the cultural roots of our ecological crises can act, though those actions may be more temporary, such as President Obama's short-lived conservation efforts when they are not followed by a parallel change in culture. The concern is, then, merely a theoretical objection, and is not grounded in experience.

ds

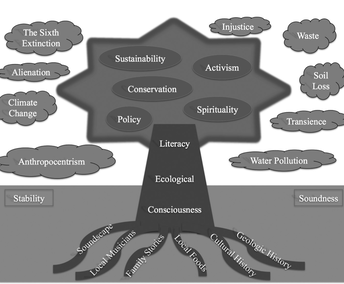

Image from Page 11 of Eco-Literate Music Pedagogy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed