Post 2.

Perhaps since when studying Western music we’re studying ideas about the West—as a culture—we ought to begin by asking ourselves, “what is ‘Western’ about the West?” That is, what is distinctive about the Western tradition, as opposed to, say, the Chinese tradition, Indian tradition, or African tradition?

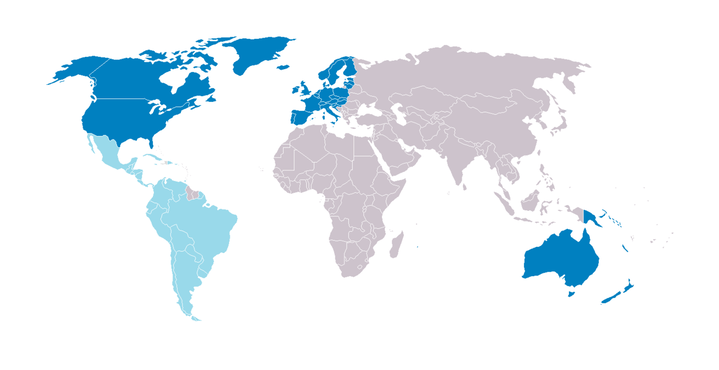

Traditionally, Western Music refers to music of the Western World. Not all of the land that makes up the West is automatically westward in direction of land in the Eastern World on a standard map. So, the West doesn’t necessarily refer to direction—at least not simply direction. Western Europe, the U.S. and Canada, Australia and New Zealand have historically been considered the West. Latin American countries are sometimes considered the West, and sometimes not (see image).

Image link: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ca/The_West_-_Clash_of_Civilizations.png/1280px-The_West_-_Clash_of_Civilizations.png

The West can refer to the following:

Which of these eight referents are relevant to our study of Western Music? All of them? Some? None? The Western canon refers to a body of cultural products, often called the classics. In philosophy this can refer to thinkers as diverse as Socrates, Seneca, Thomas Aquinas, Mary Wollstonecraft, John Dewey, and Jean Baudrillard. This is a diverse set of thinkers, but in general they tend to be (though are not always) male, bourgeoisie, and White. Similarly in literature figures include Homer, Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, Jack London, and Kurt Vonnegut. In the visual arts, figures like Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Francisco de Goya, Claude Monet, and Andy Warhol come to mind.

In music, this body of so-called “high art” is called Classical Music, Western Classical Music, Western Art Music, or just Western Music—referring to cultural products, liturgical and secular related to sound. As Western Music is traditionally conceived, it does not refer to popular music, folk music, or jazz. But why not? One phrase, Classical Music, can be confusing because classical can also refer to the classical period of Western Music (approx., 1750-1820—Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven), rather than the entire history of Western Music. Historical divisions of Western Music include:

I borrowed these dates from Wikipedia for ease. In music history texts, these divisions are by no means standard or a given—though often some sort of periodization is taken-for-granted. A historical era, in this sense, represents a group of composers and performance practices that generally hold together as logically and stylistically consistent to a historian. History is socially constructed. Historians decide which historical periods to use, and decide which composers and compositions belong in the canon. This process is fraught with bias. Even today most music history textbooks rely primarily on male composers and performers, while female composers are discussed less often.

Listening:

And God Created Great Whales, Op. 229, no. 1, performed by the Seattle Symphony

Link: https://youtu.be/1pTu4pkmtpU

Another recording, by the Youth Orchestra of San Antonio

Link: https://youtu.be/SgESUPnCQ5o

One aspect of the Western tradition that is dominant is a dichotomy between “man” and “nature.” This provides a hard division, philosophically and in practice, between what is human and what is animal. The classical philosopher and Roman statesperson Cicero (106-43 BCE) wrote of duty:

“In any consideration of duty we must remember man’s natural pre-eminence over cattle and other beasts. Animals enjoy nothing but pleasure and are directed towards it by their every impulse. The human mind, on the other hand, develops through learning and thinking. It constantly investigates or explores and is led by the delight it takes in sights and sounds. A person who is inclined to pleasure-seeking, assuming he’s not just an animal (for some people are, indeed, human in name only), but is at least a little more upright—even if he is motivated by pleasure, hides or disguises his impulse out of sense of shame.” (Habinek 2012, 142)

Following this dichotomous logic, humans make music, and animals do not. Whether conservative or liberal, traditional or change-oriented, most Western definitions of music are anthropocentric—that is, human centered. Music is something people do (see Elliott and Silverman 2015; Small 1998). We’ll revisit these definitions in the next post on Music.

However, Vandana Shiva (1952-date) and other environmental activists have challenged the West to think more ecocentrically—that is, ecology-centered. Shiva (2005) writes “All species, peoples, and cultures have intrinsic worth. … The earth community is a democracy of all life. … [and] All beings have a natural right to sustenance” (9). This ecocentric position is often found in ecological movements, such as ecofeminism and deep ecology. Ecocentrists claim that anthropocentric thinking is destroying our planet, because we fail to care sufficiently for nonhuman lifeforms and their ecosystems. We may preserve a strip of wilderness for humanity, but when that land is more useful to people as housing, or timber, or oil, ecocentrists argue that anthropocentric conservation fails. I draw from ecocentrists like Shiva to construct a more ecocentric definition of music (see Shevock 2018). The debate over anthropocentrism and ecocentrism is possible because, traditionally, Western thinkers have seen this dichotomy as essential, and have tended to value the human world above the natural world.

Following this dichotomy, humans can experience music following another dichotomy—science and phenomenal. In the West, there is often a strong dichotomy between rationality and emotion. Science draws our attention to the material aspects of sounds that make music. In a way, in science the world as experienced is somewhat illusionary. The earth travels around the sun. The object touched consists of atoms you cannot see. In physicalism—sometimes called reductionism—sociology and psychology are, as sciences, reducible to biology; biology is reducible to chemistry; and chemistry is reducible to physics. For instance, the feeling of elation experienced with friends while dancing (sociology) can be understood using psychometrics (psychology), which point toward specific parts of the brain (biology), chemical reactions (chemistry), and finally the movement of physical particles (physics). Even when this reductive scheme cannot be fully uncovered, physicalism suggests that, with time, research will eventually understand it. Science, as a way of thinking about music, is reductive and requires quite a bit of thought and study. Many scholars dedicate their life’s work to testing specific aspects of music using sociology, psychology, biology, or chemistry. It may be this reduction and thought that make this type of research beneficial to those of us trying to understand music. But limitations also arise.

One cannot describe music only from a scientific perspective. The “phenomenal” merely refers to understanding something in relation to our senses (e.g., hearing, sight, taste, touch, smell). This can be considered less scientific, unscientific, or prescientific. Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) identified this pre-scientific understanding with the term, lifeworld. In the phenomenal, we say the sun rises in the East and sets in the West (though scientifically the earth is moving, not the sun); we touch a burning frying pan and feel pain; we hear a section of music, recall a childhood memory, and are brought to tears. The lifeworld is the phenomenal world—what we experience as self-evident or given. Music is given to us through our senses, and we experience is before we begin thinking about the science of sound waves or biological function.

In 1970, the American composer Alan Hovhaness (1911-2000) composed And God Created Great Whales, which is a symphonic poem (a single movement of orchestral music suggesting a story, or other non-musical source—also called a tone poem) performed with recorded whale songs (recorded by biologist Roger Payne). The title comes from Genesis 1:21: “And God created great whales, and every living creature that moveth, which the waters brought forth abundantly, after their kind, and every winged fowl after his kind: and God saw that it was good.” In 1967, Roger Payne (1935-date) discovered whale song among humpback whales, which inspired him to join the global campaign to end commercial whaling. Payne’s influential recording inspired singer/songwriter Judy Collins’s 1970 album “Whales & Nightingales,” Kate Bush’s 1978 song “Moving,” the 1986 film “Stark Trek IV: The Voyage Home,” Paul Winter & Paul Halley’s 1987 album, “Whales Alive,” as well as Hovhaness’s composition. And in 1977, Roger Payne’s recordings were carried beyond the Solar System in the Voyager spacecraft. Scientifically, whales possess an advanced limbic system, “much more elaborate and developed than in the human brain.” According to music psychologists, the limbic system is a major part of emotional responses to music.

Questions for considerations:

References

Habinek, Thomas, trans. 2012. Cicero: On living and dying well. London: Penguin Classics.

Elliott, David J and Marissa Silverman. 2015. Music matters: A philosophy of music education, second edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Shevock, Daniel J. 2018. Eco-literate music pedagogy. New York: Routledge.

Shiva, Vandana. 2005. Earth democracy: Justice, sustainability, and peace. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

Small, Christopher. 1998. Musicking: The meanings of performing and listening. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Perhaps since when studying Western music we’re studying ideas about the West—as a culture—we ought to begin by asking ourselves, “what is ‘Western’ about the West?” That is, what is distinctive about the Western tradition, as opposed to, say, the Chinese tradition, Indian tradition, or African tradition?

Traditionally, Western Music refers to music of the Western World. Not all of the land that makes up the West is automatically westward in direction of land in the Eastern World on a standard map. So, the West doesn’t necessarily refer to direction—at least not simply direction. Western Europe, the U.S. and Canada, Australia and New Zealand have historically been considered the West. Latin American countries are sometimes considered the West, and sometimes not (see image).

Image link: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ca/The_West_-_Clash_of_Civilizations.png/1280px-The_West_-_Clash_of_Civilizations.png

The West can refer to the following:

- Western culture

- Hellenistic and Roman thought

- Christendom

- Renaissance Art

- The Enlightenment

- The Scientific Revolution

- Colonialism

- Capitalism

Which of these eight referents are relevant to our study of Western Music? All of them? Some? None? The Western canon refers to a body of cultural products, often called the classics. In philosophy this can refer to thinkers as diverse as Socrates, Seneca, Thomas Aquinas, Mary Wollstonecraft, John Dewey, and Jean Baudrillard. This is a diverse set of thinkers, but in general they tend to be (though are not always) male, bourgeoisie, and White. Similarly in literature figures include Homer, Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, Jack London, and Kurt Vonnegut. In the visual arts, figures like Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Francisco de Goya, Claude Monet, and Andy Warhol come to mind.

In music, this body of so-called “high art” is called Classical Music, Western Classical Music, Western Art Music, or just Western Music—referring to cultural products, liturgical and secular related to sound. As Western Music is traditionally conceived, it does not refer to popular music, folk music, or jazz. But why not? One phrase, Classical Music, can be confusing because classical can also refer to the classical period of Western Music (approx., 1750-1820—Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven), rather than the entire history of Western Music. Historical divisions of Western Music include:

- Ancient music (before 500 CE)

- Medieval (approx., 500-1400 CE)

- Renaissance (approx., 1400-1600 CE)

- Baroque (1600-1750 CE)

- Classical (1750-1820 CE)

- Romantic (1820-1900)

- 20th Century

- Expressionism (1908-1925)

- Impressionism (1890-1925)

- Neoclassicism (1920-1950)

- Experimentalism (1950-date)

- Minimalism (1965-date)

I borrowed these dates from Wikipedia for ease. In music history texts, these divisions are by no means standard or a given—though often some sort of periodization is taken-for-granted. A historical era, in this sense, represents a group of composers and performance practices that generally hold together as logically and stylistically consistent to a historian. History is socially constructed. Historians decide which historical periods to use, and decide which composers and compositions belong in the canon. This process is fraught with bias. Even today most music history textbooks rely primarily on male composers and performers, while female composers are discussed less often.

Listening:

And God Created Great Whales, Op. 229, no. 1, performed by the Seattle Symphony

Link: https://youtu.be/1pTu4pkmtpU

Another recording, by the Youth Orchestra of San Antonio

Link: https://youtu.be/SgESUPnCQ5o

One aspect of the Western tradition that is dominant is a dichotomy between “man” and “nature.” This provides a hard division, philosophically and in practice, between what is human and what is animal. The classical philosopher and Roman statesperson Cicero (106-43 BCE) wrote of duty:

“In any consideration of duty we must remember man’s natural pre-eminence over cattle and other beasts. Animals enjoy nothing but pleasure and are directed towards it by their every impulse. The human mind, on the other hand, develops through learning and thinking. It constantly investigates or explores and is led by the delight it takes in sights and sounds. A person who is inclined to pleasure-seeking, assuming he’s not just an animal (for some people are, indeed, human in name only), but is at least a little more upright—even if he is motivated by pleasure, hides or disguises his impulse out of sense of shame.” (Habinek 2012, 142)

Following this dichotomous logic, humans make music, and animals do not. Whether conservative or liberal, traditional or change-oriented, most Western definitions of music are anthropocentric—that is, human centered. Music is something people do (see Elliott and Silverman 2015; Small 1998). We’ll revisit these definitions in the next post on Music.

However, Vandana Shiva (1952-date) and other environmental activists have challenged the West to think more ecocentrically—that is, ecology-centered. Shiva (2005) writes “All species, peoples, and cultures have intrinsic worth. … The earth community is a democracy of all life. … [and] All beings have a natural right to sustenance” (9). This ecocentric position is often found in ecological movements, such as ecofeminism and deep ecology. Ecocentrists claim that anthropocentric thinking is destroying our planet, because we fail to care sufficiently for nonhuman lifeforms and their ecosystems. We may preserve a strip of wilderness for humanity, but when that land is more useful to people as housing, or timber, or oil, ecocentrists argue that anthropocentric conservation fails. I draw from ecocentrists like Shiva to construct a more ecocentric definition of music (see Shevock 2018). The debate over anthropocentrism and ecocentrism is possible because, traditionally, Western thinkers have seen this dichotomy as essential, and have tended to value the human world above the natural world.

Following this dichotomy, humans can experience music following another dichotomy—science and phenomenal. In the West, there is often a strong dichotomy between rationality and emotion. Science draws our attention to the material aspects of sounds that make music. In a way, in science the world as experienced is somewhat illusionary. The earth travels around the sun. The object touched consists of atoms you cannot see. In physicalism—sometimes called reductionism—sociology and psychology are, as sciences, reducible to biology; biology is reducible to chemistry; and chemistry is reducible to physics. For instance, the feeling of elation experienced with friends while dancing (sociology) can be understood using psychometrics (psychology), which point toward specific parts of the brain (biology), chemical reactions (chemistry), and finally the movement of physical particles (physics). Even when this reductive scheme cannot be fully uncovered, physicalism suggests that, with time, research will eventually understand it. Science, as a way of thinking about music, is reductive and requires quite a bit of thought and study. Many scholars dedicate their life’s work to testing specific aspects of music using sociology, psychology, biology, or chemistry. It may be this reduction and thought that make this type of research beneficial to those of us trying to understand music. But limitations also arise.

One cannot describe music only from a scientific perspective. The “phenomenal” merely refers to understanding something in relation to our senses (e.g., hearing, sight, taste, touch, smell). This can be considered less scientific, unscientific, or prescientific. Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) identified this pre-scientific understanding with the term, lifeworld. In the phenomenal, we say the sun rises in the East and sets in the West (though scientifically the earth is moving, not the sun); we touch a burning frying pan and feel pain; we hear a section of music, recall a childhood memory, and are brought to tears. The lifeworld is the phenomenal world—what we experience as self-evident or given. Music is given to us through our senses, and we experience is before we begin thinking about the science of sound waves or biological function.

In 1970, the American composer Alan Hovhaness (1911-2000) composed And God Created Great Whales, which is a symphonic poem (a single movement of orchestral music suggesting a story, or other non-musical source—also called a tone poem) performed with recorded whale songs (recorded by biologist Roger Payne). The title comes from Genesis 1:21: “And God created great whales, and every living creature that moveth, which the waters brought forth abundantly, after their kind, and every winged fowl after his kind: and God saw that it was good.” In 1967, Roger Payne (1935-date) discovered whale song among humpback whales, which inspired him to join the global campaign to end commercial whaling. Payne’s influential recording inspired singer/songwriter Judy Collins’s 1970 album “Whales & Nightingales,” Kate Bush’s 1978 song “Moving,” the 1986 film “Stark Trek IV: The Voyage Home,” Paul Winter & Paul Halley’s 1987 album, “Whales Alive,” as well as Hovhaness’s composition. And in 1977, Roger Payne’s recordings were carried beyond the Solar System in the Voyager spacecraft. Scientifically, whales possess an advanced limbic system, “much more elaborate and developed than in the human brain.” According to music psychologists, the limbic system is a major part of emotional responses to music.

Questions for considerations:

- How do ideas embedded in Western thought (such as anthropocentrism) affect Western Music?

- Do scientific descriptions or phenomenal descriptions have the final say about of experience of music?

- Since whales have an advanced limbic system, and the limbic system is connected to emotional responses to music, should whale songs be considered music?

References

Habinek, Thomas, trans. 2012. Cicero: On living and dying well. London: Penguin Classics.

Elliott, David J and Marissa Silverman. 2015. Music matters: A philosophy of music education, second edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Shevock, Daniel J. 2018. Eco-literate music pedagogy. New York: Routledge.

Shiva, Vandana. 2005. Earth democracy: Justice, sustainability, and peace. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

Small, Christopher. 1998. Musicking: The meanings of performing and listening. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed