Post 4.

Image link: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/52/Violin_%28AM_1998.60.238-3%29.jpg

Listening:

Autumn, by Tōru Takemitsu, by the WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne; Kaoru Kakizakai (Shakuhachi) and Akiko Kubota (Biwa), link: https://youtu.be/QYsZJkuDmbc

Also listen to, November Steps, for shakuhachi, biwa & orchestra, by Tōru Takemitsu performed by the Saito Kinen Orchestra, link: https://youtu.be/EzKCPrZ9ywc

Most music genres use singing, some form of movement/dance, and musical instruments. Understanding instruments used can help us understand something of the character of that genre. What does the electric guitar mean to heavy metal music, or the turntable to hip hop, the accordion to polka, or the djembe in the music of Mali? Instruments provide timbre—the tone color or sound quality we associate with specific genres. Sometimes instrument performing techniques and singing techniques share certain qualities. For instance, the jazz singer Billie Holiday sounded like a jazz saxophone or trumpet. Similarly in Western Music, classical singers often sing bel canto, which is Italian for “beautiful sound.” Singers in classical music are often categorized by voice type. Voice types take into account vocal range (how high/low a person sings), weight (how loud/soft), tessitura (do they sound better in high or low registers) and timbre, and include:

Other than the voice, common instruments used in classical music are often separated into four categories.

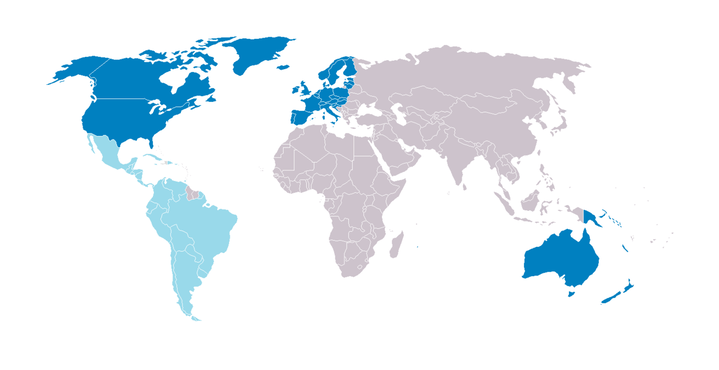

Additionally, especially since the 20th Century, composers have incorporated instruments that aren’t traditionally part of Western Music. Often this is to support the ideal of multiculturalism—the living together in tolerance of diverse cultures, including races, religious groups, and customs (including musics).

Composer Toru Takemitsu (1930-1996) wrote of the Japanese instrument, the biwa and the shakuhachi, and their differences from Western instruments. Having written for both Western and Japanese instruments, Takemitsu notes that Western instruments lend themselves to music theory—to chord structures, and scales, and notes in relation to one another. In contrast, Japanese instruments seem to demand attention to a single sound: “The sounds of such instruments are produced spontaneously in performance. They seem to resonate through the performer, then merge with nature to manifest themselves more as presence than as existence. … A single strum of the strings or even one pluck is too complex, too complete in itself to admit any theory. Between this complex sound—so strong that it can stand alone—and that point of intense silence preceding it, called ma, there is a metaphysical continuity that defies analysis. … In performance, sound transcends the realm of the personal. Now we can see how the master shakuhachi player, striving in performance to re-create the sound of wind in a decaying bamboo grove, reveals the Japanese sound ideal: sound, in its ultimate expressiveness, being constantly refined, approaches the nothingness of that wind in the bamboo grove” (Takemitsu 1995, 51).

Questions for Consideration:

References

Takemitsu, Toru. 1995. Confronting silence: Selected writings. Berkeley, CA: Fallen Leaf Press.

Image link: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/52/Violin_%28AM_1998.60.238-3%29.jpg

Listening:

Autumn, by Tōru Takemitsu, by the WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne; Kaoru Kakizakai (Shakuhachi) and Akiko Kubota (Biwa), link: https://youtu.be/QYsZJkuDmbc

Also listen to, November Steps, for shakuhachi, biwa & orchestra, by Tōru Takemitsu performed by the Saito Kinen Orchestra, link: https://youtu.be/EzKCPrZ9ywc

Most music genres use singing, some form of movement/dance, and musical instruments. Understanding instruments used can help us understand something of the character of that genre. What does the electric guitar mean to heavy metal music, or the turntable to hip hop, the accordion to polka, or the djembe in the music of Mali? Instruments provide timbre—the tone color or sound quality we associate with specific genres. Sometimes instrument performing techniques and singing techniques share certain qualities. For instance, the jazz singer Billie Holiday sounded like a jazz saxophone or trumpet. Similarly in Western Music, classical singers often sing bel canto, which is Italian for “beautiful sound.” Singers in classical music are often categorized by voice type. Voice types take into account vocal range (how high/low a person sings), weight (how loud/soft), tessitura (do they sound better in high or low registers) and timbre, and include:

- Soprano

- Some variances within soprano include the lyric soprano and the dramatic soprano

- Listen to lyric soprano Renée Fleming singing Casta Diva by Bellini, link: https://youtu.be/Rg4L5tcxFcA

- Listen to dramatic soprano Jessye Norman singing Dich Teure Halle by Wagner, link: https://youtu.be/-Tkc1gJzV4s

- Contralto (also called Alto in choirs)

- Listen to contralto Marian Anderson singing at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939, link: https://youtu.be/mAONYTMf2pk

- Tenor

- Listen to dramatic tenor Placido Domingo sing Fidelio, by Beethoven, link: https://youtu.be/HjA1GAGos-0

- Bass

- Lyric bass, listen to Feodor Caliapin singing Doubt by Glinka, link: https://youtu.be/89OhydbgC6I

- Basso profundo, listen to Yuri Wichniakovsinging with the Russian Patriarchate Choir of Moscow, link: https://youtu.be/39eBIX3PYL0

Other than the voice, common instruments used in classical music are often separated into four categories.

- Strings – violin, viola, cello, double bass

- Listen to violinist Hilary Hahn performing Caprice no. 24, by Paganini, link: https://youtu.be/gpnIrE7_1YA

- Listen to cellist Yo-Yo Ma perform Cello Suite no. 1, by Bach, link: https://youtu.be/1prweT95Mo0

- Brass – Trumpet, Trombone, Tuba, French Horn

- Listen to trumpeter Wynton Marsalis perform Carnival of Venice, (also popularized by violinist Niccolo Paganini), link: https://youtu.be/0-jDld11jhw

- Listen to Tuba player JáTtik Clark perform Concerto in F minor, by Vaughan Williams, link: https://youtu.be/3GzEvWXN3zY

- Woodwinds – flute, clarinet, oboe, bassoon

- Listen to flutist James Galloway perform Flight of the Bumblebee by Rimsky-Korsokov, link: https://youtu.be/LI3wIHFQkAk

- Listen to the Oberlin Bassoon Quartet perform music from Super Mario, by Koji Kondo, link: https://youtu.be/2gXh83hNnWw

- Percussion – timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine

- Listen to marimbist Evelyn Glennie perform the Maple Leaf Rag by Scott Joplin, link: https://youtu.be/CHBsFOl-SnA

- Listen to timpanist Daniel Druckman perform Eight Pieces for Four Timpani, by Carter, link: https://youtu.be/RtzBo1IGRYI

- Piano

- Listen to Chick Corea playing (improvising on) Mazurka op. 17, no 4, by Chopin, link: https://youtu.be/AZUiJkmtX78

Additionally, especially since the 20th Century, composers have incorporated instruments that aren’t traditionally part of Western Music. Often this is to support the ideal of multiculturalism—the living together in tolerance of diverse cultures, including races, religious groups, and customs (including musics).

Composer Toru Takemitsu (1930-1996) wrote of the Japanese instrument, the biwa and the shakuhachi, and their differences from Western instruments. Having written for both Western and Japanese instruments, Takemitsu notes that Western instruments lend themselves to music theory—to chord structures, and scales, and notes in relation to one another. In contrast, Japanese instruments seem to demand attention to a single sound: “The sounds of such instruments are produced spontaneously in performance. They seem to resonate through the performer, then merge with nature to manifest themselves more as presence than as existence. … A single strum of the strings or even one pluck is too complex, too complete in itself to admit any theory. Between this complex sound—so strong that it can stand alone—and that point of intense silence preceding it, called ma, there is a metaphysical continuity that defies analysis. … In performance, sound transcends the realm of the personal. Now we can see how the master shakuhachi player, striving in performance to re-create the sound of wind in a decaying bamboo grove, reveals the Japanese sound ideal: sound, in its ultimate expressiveness, being constantly refined, approaches the nothingness of that wind in the bamboo grove” (Takemitsu 1995, 51).

Questions for Consideration:

- According to Takemitsu, the biwa replicates the sounds of Japanese cicadas. And the shakuhachi recreates the sound of decaying wind in a bamboo grove. How does listening to this music with this in mind change how we think about music and nature?

- Close your eyes and listen to Western instruments. Do they remind you of nonhuman animals, or other aspects of nature such as the wind, rain, or waves?

References

Takemitsu, Toru. 1995. Confronting silence: Selected writings. Berkeley, CA: Fallen Leaf Press.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed